19 May Evolutive Interpretation of Proportionality and Precautions to Strengthen Protections under International Humanitarian Law

[Tadesse Kebebew is a Researcher and Project Manager at the Geneva Water Hub, a Centre of Competence on Water for Peace and holds a PhD in International Law from the Geneva Graduate Institute]

Introduction

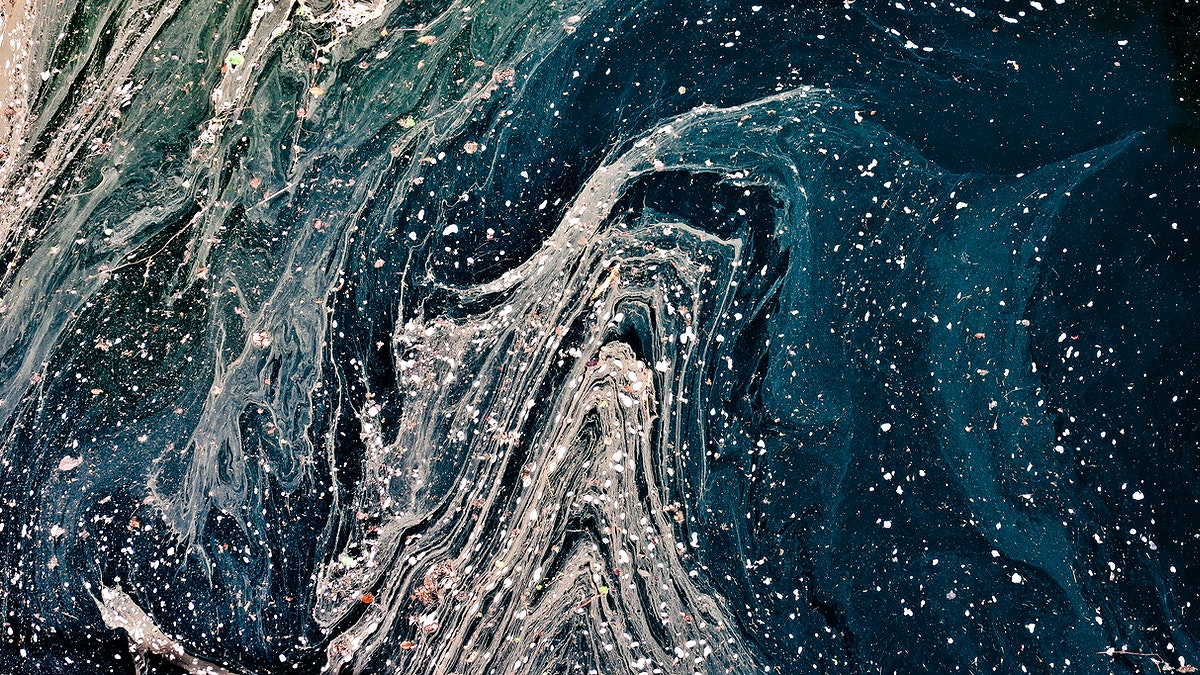

Water has increasingly become both a target and a weapon in armed conflicts across regions, causing severe humanitarian suffering and environmental degradation. When warring parties damage water systems or restrict access to water sources, civilians face immediate and long-term consequences. Excessive civilian harm and infrastructure damage, as witnessed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Gaza, can weaken military support, undermine legitimacy, fuel resentment and strengthen insurgencies. As warfare tactics evolve, so too must the frameworks governing humanitarian protections.

This piece makes the case for applying a living instrument interpretive approach, rooted in the European Court of Human Rights’ Tyrer v. UK decision, to enhance international humanitarian law (IHL) principles of proportionality and precaution in attack, using the protection of water infrastructure as an example. An adaptive interpretation of these principles in good faith, with due regard for evolving circumstances, is essential to effectively applying IHL in addressing contemporary humanitarian and military challenges. This approach reinforces the humanitarian requirements and protections central to IHL and enhances military effectiveness by minimizing collateral damage and supporting efforts to win the hearts and minds of affected communities.

The Peril of Weaponized Water: Direct, Indirect and Cumulative Impacts

As water is essential to the survival of the civilian population, protecting water is protecting civilians. Reports from armed conflicts in Syria, Gaza, Sudan, Ukraine, Burkina Faso, Libya, Yemen and beyond demonstrate the catastrophic impacts of weaponizing water on the civilian populations and the natural environment. The direct and indirect impacts outlined in the reports underscore the urgent need to reinforce compliance with the legal protections. A study at Geneva Water Hub reveals that the destruction of water and wastewater systems and the interruption of water supplies in Gaza led to hundreds of thousands of water-related diseases. Parties to an armed conflict must carefully account for the potential foreseeable impacts during their operations.

Damages to water treatment plants, pipelines and reservoirs are some of the direct impacts leading to disruptions in water supply. For instance, in Khartoum, damage to water facilities has left hundreds of thousands of residents without running water. In Syria, two-thirds of water treatment plants have been damaged, affecting millions. In Gaza, access to water has become a ‘‘matter of life and death’’, with reports indicating a dramatic 94% reduction compared to pre-war levels. Such impacts are compounded by reverberating effects such as increased exposure to waterborne diseases, forced displacement, livelihood disruptions and environmental degradation. In addition, the direct and indirect impacts can accumulate from the successive weakening of infrastructure due to repeated attacks or protracted armed conflicts, reducing community resilience and complicating post-conflict peacebuilding.

Existing International Law Protections

International law offers layers of protection for water resources and infrastructure. IHL restricts the choice of means and methods of warfare by parties to an armed conflict. It also prohibits the use of poison or poisoned weapons, including the contamination of water. In the conduct of hostilities, parties to an armed conflict must always respect the principles of distinction, proportionality and precautions. These principles extend to ensuring the protection of water-related installations vital for the civilian population, including implementing measures to minimize the impact on essential services. As per the principle of distinction, as civilian objects, water infrastructure benefits from the prohibition of direct attacks and indiscriminate attacks. Even when water infrastructure becomes a military objective, the principle of proportionality in attack prohibits launching an attack which may be expected to cause excessive collateral damage compared to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated. The military gains from targeting water infrastructure are minimal or non-existent – far outweighed by the severe consequences to civilians and the environment. The principle of precautions in attack obliges parties to a conflict to take constant care to spare water infrastructure. Those who plan, decide upon and execute attacks must do everything feasible to verify that these are military objectives and that attacks are not prohibited. And, the principle of precautions against the effects of attacks requires parties to take all feasible precautions to spare water infrastructure under their control. And, they should avoid locating military objectives in the vicinity of water infrastructure.

There are also prohibitions under the special protective regime of IHL for certain objects, including works and installations containing dangerous forces and the natural environment (including water resources), and specific methods of warfare, such as starvation and the prohibition against attacking, destroying, removing, or rendering useless objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, such as drinking water installations and supplies and irrigation works. These protections are vital because even when such objects become military objectives, they shall not be attacked save for minor exceptions.

In situations of occupation, IHL imposes additional obligations on occupying powers, such as ensuring the necessities of life for the population, maintaining public health and hygiene in the occupied territory, and mandatory relief schemes for humanitarian assistance. Occupying powers must also respect their human rights obligations, including ensuring the occupied population has access to adequate water in both quantity and quality.

In addition, as detailed in the Geneva Principles, other branches of international law also offer protection for freshwater resources and related installations. For instance, the human rights to water and sanitation are globally recognized. Water is a prerequisite for realizing other human rights, including the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment. The PERAC Principles emphasize that the environment should be respected and protected in accordance with pertinent international laws. The UNSC (S/RES/2573 (2021)) recognizes the interconnectedness of certain essential services and condemns, among others, unlawful attacks against and misuse of objects indispensable to the civilian population, including those services that are key for the provision of water and sanitation, energy, and food production and distribution. Similarly, the unanimously adopted S/RES/2417 (2018) underscores the link between armed conflict and conflict‑induced food insecurity and addresses the protection of water and water systems.

Why apply the living instrument approach?

Despite extensive protections under international law and IHL, uncertainties and indeterminacy remain in applying the principles of proportionality and precautions in attacks. Assessing compliance with these principles involves evaluating several legal factors and establishing the facts, including what was targeted, what military advantage was anticipated, and what precautionary measures were taken. Such evaluations also inevitably involve subjective value judgements. Parties to an armed conflict must consider the reasonably foreseeable effects of attacks. This view is supported by both textual and purposive interpretations of the principles of proportionality and precautions in attacks that support this position. However, the precise scope of this obligation – defining which impacts are reasonably foreseeable – remains ambiguous and must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. A significant issue arises with the cumulative impacts of repeated attacks and protracted conflicts, eroding infrastructure resilience and harming communities in ways that individual attacks may not reveal.

The living instrument approach could provide a framework to adapt COH rules to meet modern humanitarian needs and address current indeterminacies in some rules of IHL. It encourages a dynamic interpretation that considers both the evolving nature of warfare and present-day knowledge to measure and understand the direct, indirect and cumulative impacts of armed conflict on civilians, objects and the environment.

First, the COH rules regulate individual attacks or ‘a specific tactical operation’ (para.2207) but do not explicitly address cumulative harms or the long-term degradation of civilian objects. Interpreting the principles of proportionality and precaution under Additional Protocol I’s section on ‘General Protection Against the Effects of Hostilities’ in good faith and in light of modern-day realities could extend their scope to encompass cumulative impacts of attacks (not just specific tactical operations), thus strengthening civilian protections in prolonged conflicts. Such an interpretive approach could also enable us to broaden the understanding of ‘military operations’, understood to mean ‘any movements, manoeuvres and other activities whatsoever carried out by the armed forces with a view to combat’ (para.2191) to include any sustained actions by armed forces, thereby allowing cumulative impacts to be integrated into proportionality assessments. Similarly, the obligation to take ‘constant care’ (though not precisely defined in the commentary to Additional Protocol I) could provide a legal basis to include reverberating effects and cumulative harm in assessments aimed at protecting civilians.

Second, as some would argue with regard to balancing the ‘concrete and direct’ military advantage vis-à-vis incidental collateral harm and damage, the assessment of such advantage should not be limited to just a ‘target-by-target’ basis analysis but also consider the ‘overall sense against campaign objectives’. If this argument is tenable, a fortiori, the ‘overall’ incidental harm to civilians and civilian objects must also be factored into the proportionality assessment.

Third, there is also ambiguity regarding the treatment of ‘dual-use’ objects, those serving both civilian and military purposes, particularly in whether their civilian components should be considered in proportionality assessments. An interpretive approach that gives greater weight to the inclusion of civilian components would provide a more balanced perspective, aligning with the overarching principle of minimizing or avoiding collateral harm and damage.

Fourth, armed conflicts weaken infrastructure resilience and diminish the ability of population to cope with humanitarian challenges, resulting in economic decline and broader societal disruptions. These impacts must be carefully considered when planning and conducting military operations to better protect civilians. Adopting a living instrument perspective also reinforces IHL’s core objectives, requiring a nuanced understanding of its foundational purposes and better reflecting the broad impacts of war. Embracing a living instrument interpretation approach would extend the scope of IHL to address the full spectrum of harms resulting from attacks on or damages to civilian infrastructure, including access to essential services, health crises, and displacement. The benefits are twofold: protecting civilian populations and infrastructure while also enhancing military operational effectiveness by reducing backlash from affected communities. For example, adopting more robust protections for water can improve the standing of military forces among local communities and contribute to stability, thereby advancing peacebuilding efforts.

Finally, the interpretive approach contributes to upholding the obligation to ensure respect for IHL, under all circumstances, and extends to third states, which must prevent breaches, promote compliance, and avoid actions that facilitate violations. Under such an interpretation, arms-exporting states, for instance, must consider the potential reverberating effects of transferred arms in conflict zones where civilian infrastructure faces repeated attacks. Furthermore, this approach supports integrating advanced technologies in compliance efforts and can significantly improve protection efforts. Tools such as satellite imagery, drone surveillance, and predictive analytics offer insights into the status of critical infrastructure and can aid in transparent tracking, early warnings, and rapid response, thereby improving accountability for violations of IHL.

Accordingly, the living instrument interpretive approach enables addressing the indeterminacies in IHL and carefully considering the underlying objectives of the law in its interpretation and application. This entails embracing the indirect, long-term and cumulative impacts of armed conflicts. To that end, establishing clearer guidelines for proportionality and precaution assessments, particularly regarding indirect and cumulative effects, would assist decision-makers in adhering to humanitarian standards while improving strategic planning. Establishing precise guidelines and considering a total ban on the weaponization of water along with the designation of protected zones around key water infrastructure could be part of this discussion. A robust evidence base, complemented by targeted military training, is essential to ensure that the cumulative consequences of attacks on civilian infrastructure are fully understood and appropriately addressed.

Conclusion

Adopting the living instrument approach for interpreting proportionality and precautions under IHL enhances civilian protection and advances humanitarian and military objectives without reinventing the wheel. By accounting for indirect, cumulative and reverberating effects on essential resources like water, this approach not only limits civilian suffering but also supports military objectives by reducing local hostility and aiding post-conflict recovery. As modern conflicts increasingly involve water and other vital resources, interpreting IHL to meet these evolving challenges is crucial for effective protection, community resilience and stability.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.