04

Feb

Author: Karen Alter, Larry Helfer and Jacqueline McAllister

03

Feb

AJIL Symposium: Introduction to “A New International Human Rights Court for West Africa: The ECOWAS Community Court of Justice”

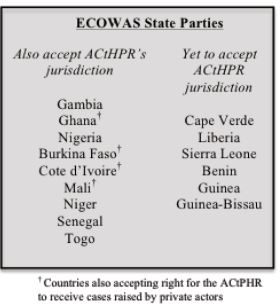

[Karen J. Alter is Professor of Political Science and Law at Northwestern University, Laurence R. Helfer is the Harry R. Chadwick, Sr. Professor of Law at Duke University, and Jacqueline McAllister is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Kenyon College (as of July 2014).] The ECOWAS Community Court of Justice is an increasingly active and surprisingly bold adjudicator of human rights cases. Since acquiring a human rights jurisdiction in 2005, the ECOWAS Court has issued more than 50 decisions relating to alleged rights violations by 15 West African states. The Court’s path-breaking cases include judgments against Niger for condoning modern forms of slavery, against Nigeria for impeding the right to free basic education for children, and against the Gambia for the torture of dissident journalists. A New International Human Rights Court for West Africa: The ECOWAS Community Court of Justice, recently published in AJIL, explains how a sub-regional tribunal first established to help build a common market was later redeployed as a human rights court. We investigate why West African governments—which set up the Court in a way that has allowed persistent flouting of ECOWAS economic rules—later delegated to ECOWAS judges a remarkably expansive human rights jurisdiction over suits filed by individuals and NGOs. Our theoretical contribution explains how international institutions, including courts, evolve over time in response to political contestation and societal pressures. We show how humanitarian interventions in West Africa in the 1990s created a demand to expand ECOWAS’s security and human rights mandates. These events, in turn, triggered a cascade of smaller reforms in the Community that, in the mid-2000s, created an opening for an alliance of civil society groups and supranational actors to mobilize in favor of court reform. The creation of a human rights court in West Africa may surprise many readers of this blog. Readers mostly familiar with global bodies like the ICJ, the WTO and the ICC, or regional bodies in Europe and the Americas, may be unaware that Africa also has active international courts that litigate important cases. Given that ECOWAS’ primary mandate is to promote economic integration, we wanted to understand why its court exercises such far-reaching human rights jurisdiction. Given that several ECOWAS member states have yet to accept the jurisdiction of the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights, the ECOWAS Court’s ability to entertain private litigant complaints—without first requiring the exhaustion of domestic remedies—is especially surprising. We also expected that even if ECOWAS member states decided to create such a tribunal, they would have included robust political checks to control the judges and their rulings.

What we found—based on a review of ECOWAS Court decisions and more than two dozen interviews with judges, Community officers, government officials, attorneys, and NGOs—was quite different. The member states not only gave Court a capacious human rights jurisdiction, they also rejected opportunities to narrow the Court’s authority.

Our AJIL article emphasizes several interesting dimensions of the ECOWAS Court’s repurposing and subsequent survival as an international human rights tribunal.

We also expected that even if ECOWAS member states decided to create such a tribunal, they would have included robust political checks to control the judges and their rulings.

What we found—based on a review of ECOWAS Court decisions and more than two dozen interviews with judges, Community officers, government officials, attorneys, and NGOs—was quite different. The member states not only gave Court a capacious human rights jurisdiction, they also rejected opportunities to narrow the Court’s authority.

Our AJIL article emphasizes several interesting dimensions of the ECOWAS Court’s repurposing and subsequent survival as an international human rights tribunal.