29 Dec Some Thoughts on Samuel Huntington’s Passing: Imperial History, Contemporary Elections, and Normative Borders

With Samuel Huntington’s passing on December 24th, I thought I’d post something on his “clash of civilizations” theory. Then I came across the following couple of posts from Strange Maps that not only relate to Huntington’s interests, but are quite interesting in their own right. They illustrate the ongoing interrelation of geography, culture, and historical boundaries on modern domestic and international relations. Without ratifying the whole idea of a clash between civilizations, they do show the ongoing relevance of the geopolitical (and geocultural) perspective.

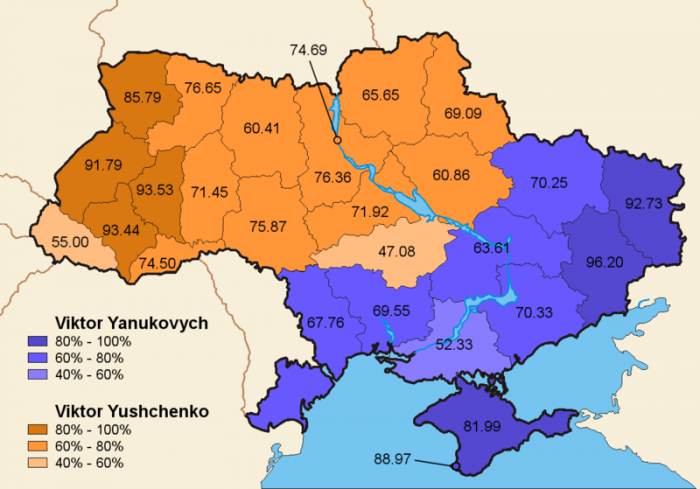

The first post shows a sort of electoral dividing line within Ukraine. In the 2004 electoral battle of the two Viktors (the Russia-leaning Yanukovich and the Western-leaning Yushchenko), each candidate carried a geographically contiguous area:

[Image Courtesy of Strange Maps]

The analysis at Strange Maps included the following:

The 2004 ‘Orange Revolution’, in which pro-western candidate Viktor Yushchenko successfully contested the rigged results of the presidential election that was ‘won’ by his pro-Russian opponent Viktor Yanukovich, seemed to place the Ukraine firmly in the western camp. Ukrainian politics has however seen several reversals of fortune since that time, proving that Ukraine is unique among the former Soviet republics: pro-western and pro-Russian sentiments are almost completely in balance.

That balance is not spread out evenly across the country. This map shows which of both Viktors was the victor in each of Ukraine’s regions in the (contested) November 2004 presidential elections. Each candidate has won in a remarkably contiguous area – Yushchenko winning the northwestern half of the country, Yanukovich the southeastern part. Both Moscow and the West are eager to have the populous, and potentially prosperous Ukraine in their camp. Will the fault line running through the Ukraine become the front line of a Second Cold War?

I hope it will not come to that, but in any case, this re-emphasizes the interplay of geography, culture, and politics. The electoral dividing line as a proxy for a deeper normative border.

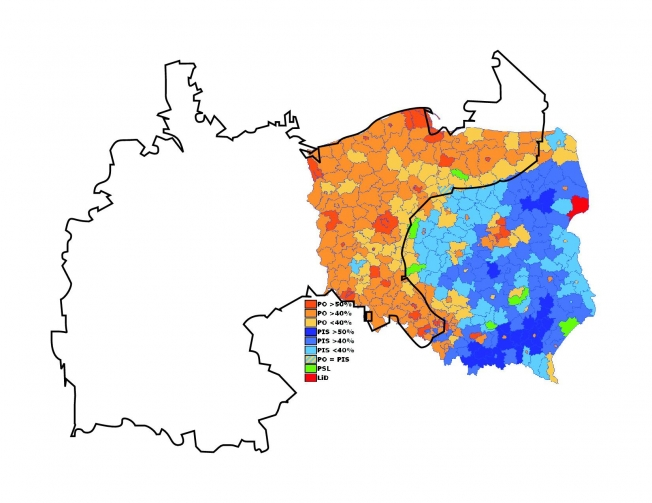

However, while the Ukraine map is interesting, it is not all that surprising. For an example that is more surprising (to me at least), and may be evidence of the important role of historical borders in defining current culture and politics, see the later post, An Imperial Palimpsest on Poland’s Electoral Map. The post begins as follows:

“Your map showing the electoral divide in Ukraine (#343) is quite interesting, and put me in mind of a similar one that I saw last year, that prompted me do a bit of map research,” writes David G.D. Hecht. “If you look at the Wikipedia article on the Polish legislative elections of 2007, there is a map there similar to the Ukrainian one. I looked at this map and thought, hmmm…where have I seen this divide before? Looks very familiar. This isn’t just some urban/rural, professional/worker, white-wine-and-brie/beer-and-sausages thing!”

Mr Hechtdid some overlay work, and came up with this remarkable fit: “The divide between the (more free-market) PO and the (more populist) PiS almost exactly follows the old border between Imperial Germany and Imperial Russia, as it ran through Poland! How about that for a long-lasting cultural heritage?!?” How about: amazing, bordering on the unbelievable?

Here’s the overlay:

This is not to say that “Huntington was right.” While I think there is much about which he was in error in his “Clash of Civilizations” thesis (in particular its rather conflictual sense of “the West versus the rest,” as Edward Said put it), I do think Huntington did play an important and useful role in helping return geography and culture to the forefront of discussions of international relations.

Aspects of Huntington’s theory (as well as insights by others using a geopolitical perspective) can affect the work of international lawyers to the extent that it takes what we may have accepted as universal “givens” (be they assumptions as to rights, responsibilities, or the very function of international law) and contends that these supposed givens are actually open questions and sources of conflict across cultures. In light of this, I have suggested that international lawyers may want to consider the role of what I call systemic borderlands (states that are the geopolitical crossroads between two or more normative orders) and of normative friction (the process by which competing conceptions of public order interact in these borderland states). I think that part of bringing geopolitical perspective to international law means trying to map (literally and figuratively) the spread of norms and compare/contrast the map of those norms to the architecture of the international legal system. More on that in future posts.

For now, though, we remember Samuel Huntington, who wasn’t always right (who is?) but was consistently thought-provoking.

The Polish map doesn’t make sense because of the considerable migration that has been going on since the collapse of Imperial Germany. For example, in parts of the most western parts of Poland a majority of Poles are descended from eastern Poles who were expelled by the Soviets in 1945-6 and resettled on land taken from Germany (after the Germans were expelled). The real explanation is in fact urban/rural (the correlation is very strong). Rural areas have suffered most from the transition to market capitalism. Urban areas – particularly those near the German border benefited from foreign investment (especially German investment) to a much higher degree than eastern parts of the state. In Ukraine the map seems to break down on the basis of ethnicity but that’s because Yushenko was campaigning on an anti-Russia platform that couldn’t possibly have won him support in Russian parts of the country. The parts of the country won by Yanukovych are wealthier and tied into the Russian economy. Given the relatively low rates of foreign investment into Western Ukraine it made sense at the time (in the short-term) to pander to Western hostility towards Russia in the hopes of attracting money. Culture is good… Read more »

I have much the same thought as Chris. When the article and book came out in the mid 1990s, I brushed it off, deeply committed to not just a moral view of human rights universalism, but to an empirical thesis that it was transgeographical, transcultural and transhistorical as a set of values. I am much more chastened now as to the endurance of culture and religion and the profound particularity of much of what I took for granted as “universal.” Fouad Ajami has a good appreciation of Huntington in today’s WSJ, at what I think is an open link here:

http://sec.online.wsj.com/article/SB123060172023141417.html

[…] Opinio Juris and South Jerusalem both featured commentary on Huntington’s legacy this week. Possibly […]

I am so sad to hear of Prof. Huntington’s passing away. I thought that some subsequent authors misunderstood his interpretation of the potential for a clash of civilizations. I guess we read into it what we want. Anyway he was an inspiration to me in some ways, as I understood the impetus for his writing the book.