[Dr. Horace S. Adjolohoun is a Senior Legal Expert at the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. He recently completed his LLD thesis on Giving Effect to the Human Rights Jurisprudence of the ECOWAS Court of Justice: Compliance and Influence

at the University of Pretoria.]

I agree with Alter, Helfer and McAllister that progressive judicial lawmaking may be risky, particularly in an environment where domestic politics are not in favor of a supranational court that limits the sovereignty margin of state organs. In the context of the ECOWAS Court of Justice (ECCJ), an interesting question could therefore be whether, by a purposive adjudication, the Court could read community law through its human rights mandate. The Court has repeatedly given a negative answer, and many have warned of the related risks, particular bearing in mind the fall of the SADC Tribunal. An association of factors makes me suggest that the chance could be worth taking.

The ECCJ is the official judicial body in which ECOWAS has vested the mandate to oversee the interpretation and application of norms adopted under the aegis of the Community (‘original’ Community law). I suggest that the African Charter has acquired the status of Community law because of its 'constructive' incorporation in ECOWAS instruments, particularly the 1993 Revised Treaty and the 2001 Governance Protocol. On the basis of the 2005 Court Protocol, the ECCJ has confirmed that status through its successive human rights judgments, starting from the first one in 2005. Article 31(1) VCLTTreaty law commands that interpretation of conventions should follow the ordinary meaning and not expand beyond the initial intention of the parties. Particularly, in the framework of regional integration arrangements, the ‘agency’ doctrine suggests that the Agent (here the ECCJ) may not usurp legislative functions by either interpreting the silence of the law in a particular direction (which I argue the ECCJ did in the

Ugokwe case) or – and thereby – generating new norms that were not expressly formulated by law-makers (here, state parties) (see

Stone Sweet, 10-15). Some of the authors of the lead article support that approach in a

previous work.

I agree that the silence of the 2005 Protocol regarding the well established international customary law rule of exhaustion of domestic remedies is as plain as was the lack of direct access for private litigants in the

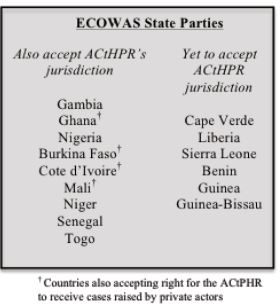

Afolabi era. Despite this, the ECCJ’s judges espoused purposive – and, in my view, ‘progressive’ – judicial lawmaking regarding exhaustion. The ECOWAS human rights ‘regime’ borrows from the African Charter-based system, which poses seven admissibility requirements for complaints to be accepted by the African Court and Commission. In the practice of the Commission, the rule of exhaustion is by far the one that attracts more contention. The 2005 ECCJ Protocol provides for ‘non-anonymity’ and ‘non-pendency’ as the two admissibility conditions.

From the foregoing, it is surprising that, in the course of lawmaking, ECOWAS states provided expressly for two ‘minor’ conditions, and remained silent for a ‘major’ condition, which has always attracted dispute.

We also expected that even if ECOWAS member states decided to create such a tribunal, they would have included robust political checks to control the judges and their rulings.

What we found—based on a review of ECOWAS Court decisions and more than two dozen interviews with judges, Community officers, government officials, attorneys, and NGOs—was quite different. The member states not only gave Court a capacious human rights jurisdiction, they also rejected opportunities to narrow the Court’s authority.

We also expected that even if ECOWAS member states decided to create such a tribunal, they would have included robust political checks to control the judges and their rulings.

What we found—based on a review of ECOWAS Court decisions and more than two dozen interviews with judges, Community officers, government officials, attorneys, and NGOs—was quite different. The member states not only gave Court a capacious human rights jurisdiction, they also rejected opportunities to narrow the Court’s authority.