[Jonathan Hafetz is an Associate Professor of Law at Seton Hall University School of Law. This post is written as a comment to Stuart Ford's guest post, published yesterday.]

Stuart Ford’s article, Complexity and Efficiency at International Criminal Courts, seeks to address the common misperception that international criminal trials are not only expensive, but also inefficient. Professor Ford’s article focuses principally on the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), which, in terms of the total number of accused, is the largest international criminal tribunal in history. Professor Ford seeks to measure whether the ICTY has, in effect, provided good bang for the buck. He concludes, rightly I believe, that it has. Although his primary aim is to develop a way for measuring a tribunal’s efficiency, Professor Ford’s article also has important implications for broader debates about the merits of international criminal justice.

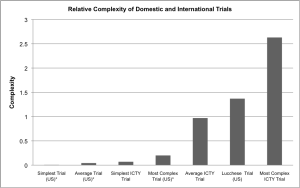

Professor Ford defines efficiency as the complexity of a trial divided by its cost. While trials at the ICTY often have been long and expensive, they have also been relatively efficient given their complexity. Further, the ICTY preforms relatively well compared to other trials of similar complexity, such as terrorism trials conducted in the United States and Europe, as well as trials that are somewhat less complex, such as the average U.S. death penalty case. Garden-variety domestic murder trials, which at first blush might appear more efficient than the ICTY, do not provide a useful point of comparison because they are much more straightforward.

Once complexity is factored in, the ICTY appears comparatively efficient. Its record is more impressive considering that an often recognized goal of international criminal justice—creating a historical record of mass atrocities—can make the trials slower and less efficient in terms of reaching outcomes for specific defendants.

Professor Ford also finds that the ICTY performed more efficiently than the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), thus challenging a perceived advantage of such hybrid tribunals over ad hoc tribunals like the ICTY. His conclusion suggests the need for future research on comparisons among tribunals within the international criminal justice field, which might have implications from an institutional design perspective.