[Annie Gell is the Leonard H. Sandler fellow in the International Justice Program at Human Rights Watch]

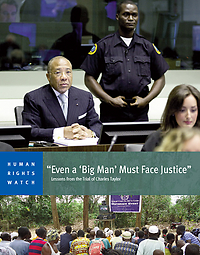

Yesterday, Human Rights Watch released the report

“Even a ‘Big Man’ Must Face Justice”: Lessons from the Trial of Charles Taylor. It examines the conduct of Taylor’s trial at the

Special Court for Sierra Leone (“SCSL”), the court’s efforts to make its proceedings accessible to affected communities, and perceptions and initial impact of the trial in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

The aim of the report is to draw lessons to promote the best possible trials of high-level suspects who are implicated in genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. It is based on interviews in The Hague, London, Washington, DC, New York, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, as well as review of expert commentary, trial transcripts, and daily reports produced by trial observers.

This post focuses on Human Rights Watch’s analysis of the trial’s conduct and lessons learned for future proceedings.

Yesterday, Human Rights Watch released the report “Even a ‘Big Man’ Must Face Justice”: Lessons from the Trial of Charles Taylor. It examines the conduct of Taylor’s trial at the Special Court for Sierra Leone (“SCSL”), the court’s efforts to make its proceedings accessible to affected communities, and perceptions and initial impact of the trial in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

The aim of the report is to draw lessons to promote the best possible trials of high-level suspects who are implicated in genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. It is based on interviews in The Hague, London, Washington, DC, New York, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, as well as review of expert commentary, trial transcripts, and daily reports produced by trial observers.

This post focuses on Human Rights Watch’s analysis of the trial’s conduct and lessons learned for future proceedings.

Yesterday, Human Rights Watch released the report “Even a ‘Big Man’ Must Face Justice”: Lessons from the Trial of Charles Taylor. It examines the conduct of Taylor’s trial at the Special Court for Sierra Leone (“SCSL”), the court’s efforts to make its proceedings accessible to affected communities, and perceptions and initial impact of the trial in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

The aim of the report is to draw lessons to promote the best possible trials of high-level suspects who are implicated in genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. It is based on interviews in The Hague, London, Washington, DC, New York, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, as well as review of expert commentary, trial transcripts, and daily reports produced by trial observers.

This post focuses on Human Rights Watch’s analysis of the trial’s conduct and lessons learned for future proceedings.