[Chimène Keitner is Harry & Lillian Hastings Research Chair and Professor of Law at the University of California Hastings College of the Law, and an Adviser on Sovereign Immunity for the American Law Institute’s Fourth Restatement of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States.]

The

judgment issued by the Fourth Section of the European Court of Human Rights represents the latest installment in an ongoing conversation about the immunity

ratione materiae of individuals accused of abusing their authority to commit serious violations of international law. As Philippa Webb has

noted over at EJIL Talk!, the Chamber found the U.K. House of Lords’s analysis of the relationship between State immunity and foreign official immunity sufficiently persuasive to conclude that, despite patchy precedents and evolving trends, “[t]he findings of the House of Lords [in

Jones v. Saudi Arabia] were neither manifestly erroneous nor arbitrary” (para. 214). My colleague William Dodge has blogged

here about flaws in the Chamber’s reading of national case law, which repeats errors made by the House of Lords that I have discussed

here and

here. These critiques amplify those enumerated by Judge Kalaydjieva in her dissenting opinion.

Although Philippa’s point about the Chamber’s “re-integration” of State and official immunity certainly holds true in the context of civil proceedings (based on the Chamber’s acceptance of the argument that any civil suit against an individual for acts committed with state authority indirectly—and impermissibly—“implead” the State), the Chamber seems to have accepted Lord Bingham’s assertion (cited in

Jones para. 32) that because “[a] State is not criminally responsible in international or English law, [it] therefore cannot be directly impleaded in criminal proceedings.” This excessively formalistic (and in some legal systems untenable) distinction led the Chamber to accept the proposition that, absent civil immunity for foreign officials, “State immunity could always be circumvented by suing named officials” (para. 202). Yet domestic legal systems have long found ways of dealing with this problem, for example by identifying whether the relief would run against the individual personally or against the state as the “real party in interest” (as the U.S. Supreme Court noted in

Samantar).

As Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers, who participated in the House of Lords’s decision in

Pinochet (No. 3) and in the Court of Appeal’s decision in

Jones v. Saudi Arabia, wrote in his

concurrence in the Court of Appeal (at para. 128): “the argument [that the state is indirectly impleaded by criminal proceedings, which was rejected in

Pinochet] does not run in relation to civil proceedings either. If civil proceedings are brought against individuals for acts of torture in circumstances where the state is immune from suit

ratione personae, there can be no suggestion that the state is vicariously liable.

We also expected that even if ECOWAS member states decided to create such a tribunal, they would have included robust political checks to control the judges and their rulings.

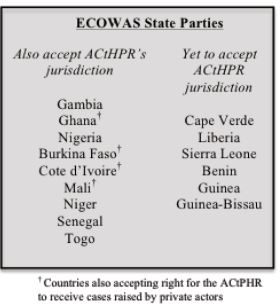

What we found—based on a review of ECOWAS Court decisions and more than two dozen interviews with judges, Community officers, government officials, attorneys, and NGOs—was quite different. The member states not only gave Court a capacious human rights jurisdiction, they also rejected opportunities to narrow the Court’s authority.

We also expected that even if ECOWAS member states decided to create such a tribunal, they would have included robust political checks to control the judges and their rulings.

What we found—based on a review of ECOWAS Court decisions and more than two dozen interviews with judges, Community officers, government officials, attorneys, and NGOs—was quite different. The member states not only gave Court a capacious human rights jurisdiction, they also rejected opportunities to narrow the Court’s authority.